The Book of Jobbed #2: A Brief History of Animals Playing Football in Movies

Air Bud's Not the Only One

The animal-as-athlete genre can be traced back to 1952 with a movie that Ronald Reagan passed on because he thought the premise was too ridiculous.

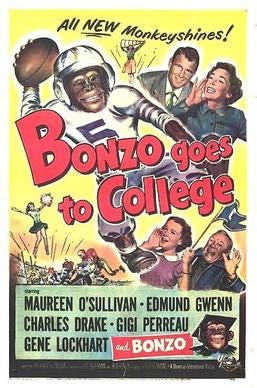

I’m of course referring to Bonzo Goes to College, which focuses on a college football coach so desperate for a win that he puts in a chimp—the titular Bonzo—at quarterback. It’s the sequel to Bedtime for Bonzo. This was the poster:

The original Bonzo film followed a psychology professor (played by Reagan) trying to teach human morals to a chimp in order to prove that the answer to the nature-versus-nurture problem is nurture, and he’s doing this to prove he is nothing like his criminal father. It asks deep, probing questions. What maketh a man? Do the sins of a father descend upon his children? Is it funny when you throw stuff at Ronald Reagan?

Bonzo Goes to College is not quite as thematically rich. It only asks one question: “if a monkey can throw poop, can a monkey throw a post route?”

The answer is yes. After Bonzo’s performance as a golfer impresses a college football coach, the coach goes to the university president and points out there is no rule that says a football player can’t be a chimpanzee. He pleads with the university president to let Bonzo take an entrance exam.

And Bonzo passes it with flying colors. The professor who proctored the exam delivers the results to the president and gives what is inarguably one of the greatest monologues in all of cinema:

“Don't ask me to explain it. I should prefer to believe the entire incident was an optical illusion.

“The fact remains that he is a straight-A scholar. His answers give every evidence of outstanding native intelligence, plus a phenomenal memory. In all honesty, he is mentally equipped to be a professor rather than a student.

“And now, if you'll permit me, I should like to resign.

After leading a renown scholar to give up on his career and presumably drink himself to death, Bonzo spearheads an explosive offense in practice. He can not only throw it long, but he’s a dual threat too. He can run it for chunk yardage at any moment. Before even playing a game, the hype gets so big that it affects the betting markets.

In the low point leading into its third act, a pair of racketeers kidnap Bonzo, swapping him with an identical chimp. Their motive is straightforward: money. They go to a bookie and put in a large bet on Pawlton’s opponent in the upcoming game.

It looks like this plan is going to work for a while. With a befuddled, turnover prone chimp in at QB, Pawlton can’t advance the ball, and their opponent runs up the score.

But Bonzo manages to escape captivity after his kidnappers go to a bookie’s bar to listen to the game on the radio. He hitches a ride in a taxi, puts on the pads, and gets back onto the field for the fourth quarter. He engineers a rally more heroic than any of Tom Brady’s 46 fourth quarter comebacks—he even wins the game by catching a touchdown pass on the final play of the game, predating the infamous Philly Special by over sixty years.

Still, the offenses of the 1950s were not nearly as sophisticated as modern day playbooks. They did not have RPOs, option routes, or zone reads out of shotgun formations. So Bonozo’s success is impressive but it doesn’t put him in the same league as quarterbacks like Lamar Jackson, Andrew Luck, and Joe Burrow.

It should also be noted that there are three big officiating problems in this movie.

Bonzo is running forward before the ball is snapped on the final play of the game. This should be flagged as illegal motion, the touchdown nullified, and the down replayed. It is a ludicrously blatant foul, and I cannot believe the refs missed this one.

On the same play, Bonzo climbs up the goalposts in order to catch the ball. It’s unclear to me whether or not this would count as being inbounds when he makes the reception, but I feel like at the very least could be a unsportsmanlike conduct foul.

Most importantly, though, the chimp acting as Bonzo’s body double is not a registered student-athlete. Pawlton, then, played an ineligible player for the majority of the game. The film makes a big deal out of the sanctity of amateurism, so I can only assume the officials don’t bring this up in the movie because they’re incompetent.

I’ll be reaching out to the NCAA and other sources to confirm whether or not the touchdown should have counted and if Pawlton University would be required to vacate the victory due to the non-student athlete the team had in at quarterback while Bonzo was kidnapped. “Watch this space,” as they say.

Gus (1976)

It took 24 years before an animal played football on the big screen again. It’s unclear why. Perhaps no one could settle on which other animals could play the sport. Maybe filmmakers thinking of making their own foray into the genre watched Bonzo Goes to College and wept for there was no point in trying to repeat a masterpiece. Perhaps the beancounters determined there wasn’t enough support in the international box office for a gridiron football movie.

Whatever the case, no one had the gumption to roll the dice on repeating the magic of Bonzo Goes to College until Walt Disney Productions gave the world Gus, a slapstick comedy about a struggling NFL team—the California Atoms—who, in their quest for a Super Bowl, sign onto the roster a mule capable of kicking 100-yard field goals and the mule’s Yugoslavian handler, Andy. Andy has an American accent for some reason but is thankfully not characterized as a communist stereotype.

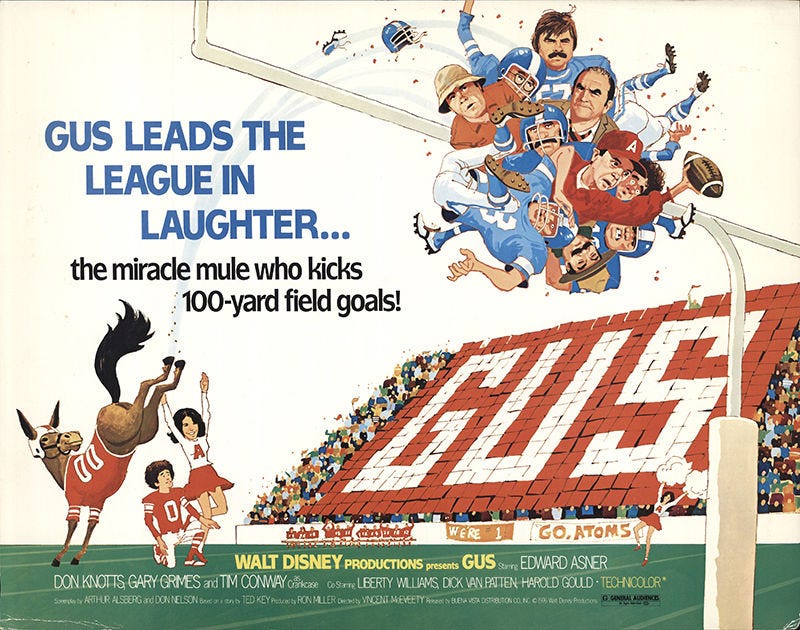

This was the poster:

Don Knotts plays the inept head coach who never makes a football decision and is only seen telling the offense, defense, or kicking units when to run out onto the field. The team is portrayed as woefully inept, so it is entirely possible that they don’t actually know when they’re supposed to be playing.

All actual decisions are made by the team owner, who is played by Ed Asner and is deeply in debt to an unscrupulous creditor implied to run an illegal sports book. The creditor, however, agrees to wipe the owner’s slate clean if the Atoms manage to improve on their 0-14 record by winning the Super Bowl.

Gus puts the team onto a championship trajectory, and the team at one point reaches first place in the standings. It’s implied, but never outright stated, that the Atoms never score a touchdown and instead kick a field goal every time they possess the ball. In one game, Gus is said to have kicked 14 field goals (doubling the record at the time).

As an aside, it’s worth noting that the Atoms secure their spot in the playoffs after beating the Buffalo Bills. The Bills, of course, were led at the time by O.J. Simpson at the time. Simpson does not make an appearance in the movie, but real life linebacker and amateur Rob Reiner lookalike Dick Butkus plays a player whose girlfriend dumps him for Andy.

Asner’s creditor resorts to hiring two conmen to sabotage Gus and Andy. The conmen first disguise themselves as drivers who intentionally take Gus and Andy around the Hollywood Hills, pretending to have gotten lost on their way to the stadium. The owner responds by hiring a security detail for Gus and Andy.

But the guards are not particular bright. The conmen easily dupe them into jumping into a field of cactuses around the stable Gus is housed in, and then proceed to pour a bottle of liquor into Gus’s feed, getting him drunk before a game. But it does not affect his game performance. This comes as no surprise since NFL players at the time regularly got hammered and snorted coke before, during, and after games. It’s not entirely clear what the conmen were expecting.

Eventually the conmen try to kidnap Andy before a game, posing as doctors at a hospital and duping him into thinking his obligatory romantic interest has been severely injured in a car accident. Andy realizes the deception, escapes, and arrives at the Atoms’ stadium just in time to see Gus kick a game winning field goal with the romantic interest acting as Gus’s placeholder.

The conmen’s next move is to kidnap Gus himself on the eve of the Super Bowl, which is being played in the Los Angeles Coliseum between the Atoms and another fictional NFL team called the Michigan Mammoths. Gus escapes captivity, resulting in a chase and a series of Looney Toon gags in a grocery store.

Hearing word of a mule running rickshaw through the San Fernando Valley, Andy and the Atoms’ hop in a helicopter and search for him, airlifting the mule from the grocery store parking lot just in time for the fourth quarter of the Super Bowl.

Gus kicks five straight field goals to get the score to 15-16. A goal line stand from the Atoms’ defense gets them the ball back on their own one-yard line with three seconds left on the clock.

This is awful coaching on the part of the Mammoths. If they just kicked a field goal instead of reaching for a touchdown, they would have gone up by four points and effectively sealed the game.

At any rate, Gus and Andy go onto the field to try for a game winning field goal. Gus, however, collapses, presumably from exhaustion, forcing Andy to make a mad dash across the field for a touchdown, securing the win and the Vince Lombardi Trophy.

Miraculously, there are no major officiating gaffes in the movie. It features a cameo from a deeply bored, annoyed, and clearly-only-in-this-for-the-paycheck Johnny Unitas (a CBS color commentator generally considered the greatest quarterback of the era), who is handed a piece of paper which goes into ludicrous detail about how the NFL rulebook does not explicitly forbid mules from being on a roster.

The movie also seems to imply that there is no formal player registration system in the 1970s NFL. I’m not sure if this is accurate but with all the cocaine and booze floating around I wouldn’t be surprised.

Air Bud: Golden Receiver (1998)

In the animal-as-athlete genre, the legal maxim “everything which is not forbidden is allowed” reigns supreme. Clearly.

It’s best illustrated by the original Air Bud, which features a scene with a referee checking the rulebook and saying, “he’s right, there ain’t no rule that says a dog can’t play basketball.”

It would be reasonable to assume that where there is not a rule explicitly forbidding an action, there are implied norms which make unnecessary specifically enumerating that you’re not supposed to do it. For example, I regularly like to remind people that there ain’t no rule that says a dog can’t be on the Supreme Court, but if anyone were to try that, it would surely be rejected out of hand as unconstitutional—though a better nomination than Robert Bork.

In cases where a norm is successfully violated, the smart and reasonable counter move is to enact a rule codifying the norm. I assume this is why Air Bud never plays the same sport in more than one movie. Because the people in charge of organizing each sport he plays fix the loophole during the offseason, enumerating that all players must be homo sapiens.

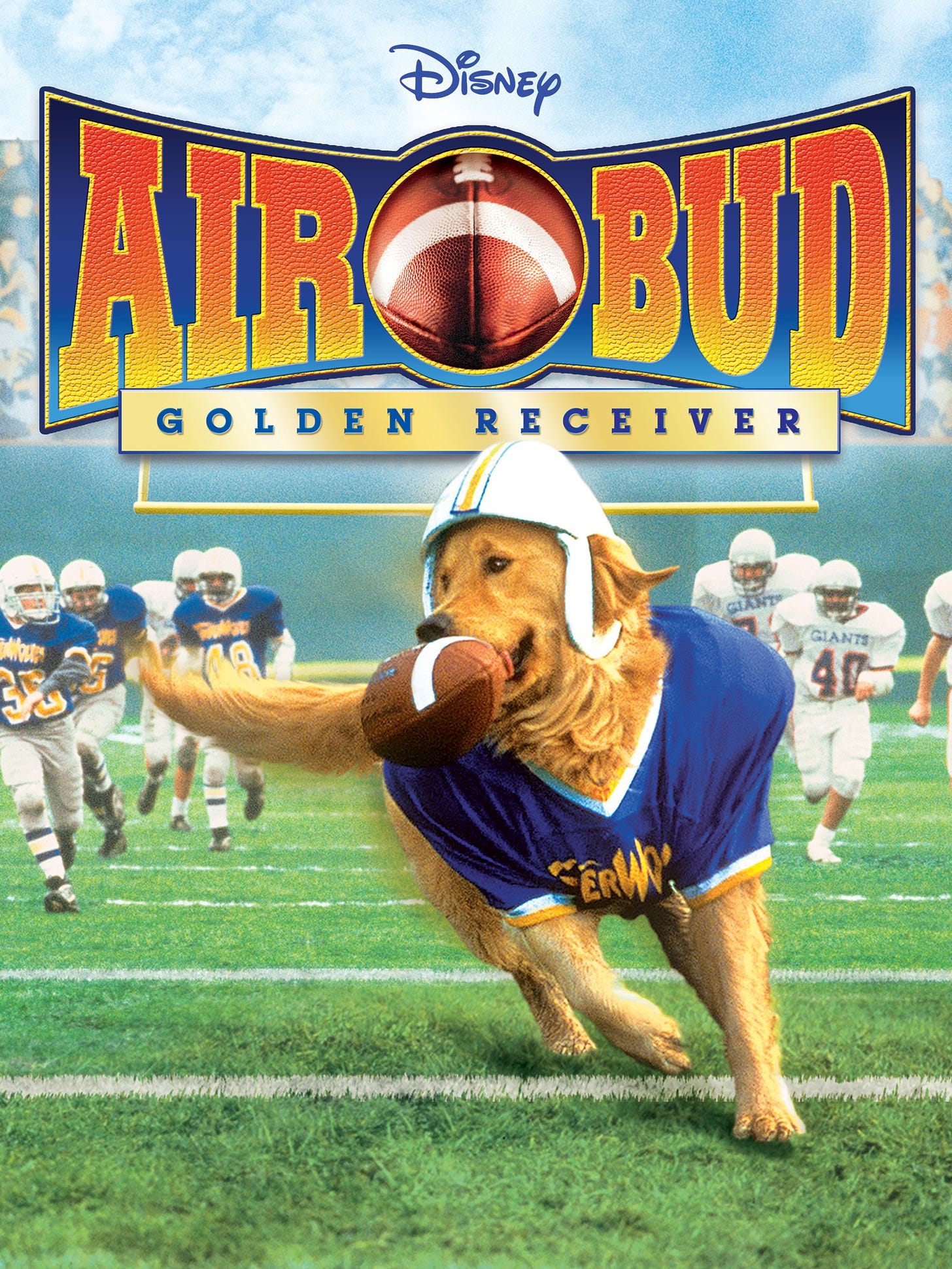

Evidently nobody in charge of football in the Air Bud cinematic universe considered getting a jump start on closing its no-rule-says-dogs-can’t-play-football loophole because this was the first sequel:

The plot follows the same general contours as Bonzo Goes to College and Gus. There’s a team that is really, really bad at football. A magical animal is discovered to have a bizarre, borderline divine predilection for the sport (in this case Air Bud is an incredible slot receiver). The team discovers that there ain’t no rule saying an animal can’t play football. The magical animal’s skills allow the team to go on a winning streak and make the championship game, but a pair of lowlife criminals kidnap the animal. The animal escapes just in time to help the team stage a come from behind victory.

Where Air Bud: Golden Retrieves zigs where the other two movies zag is that the kidnappers are not motivated by a wager they are trying to fix. Instead, they’re Russians who want to sell Air Bud to the circus.

They are essentially Rocky and Bullwinkle’s Boris Badenov and Natasha Fatale, but since this is several years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, they are not motivated by communist ideology or a desire to please Fearless Leader. They’re just capitalists of the crassest kind, utterly incapable of appreciating the finer things in life, like how good a route runner Air Bud is.

Although with the way the movie is shot and edited, it’s actually quite difficult to figure out what kind of routes Air Bud is running. His very first catch comes on a smooth and deliberately run stick route, though, so I think it’s safe to say he’s an artesian on the level of Julian Edelman.

There are also moments where Air Bud lines up as the tailback (get it). He both takes the ball on handoffs and runs as a receiver from out of the backfield, so there’s a bit of Reggie Bush to his game too. He’s undoubtably a five star recruit if he can overcome the injury he sustains near the end of the championship game.

The Future of the Genre

To my knowledge, no major or minor Hollywood player has made a movie about an animal playing football since 1998, and no one currently has such a project on their slate.

It’s entirely possible it’s because the game has evolved to such a point that no audience can be reasonably expected to suspend their disbelief and pretend that an animal is capable of comprehending the complexities of a pro-style offense or the man-on-demand defensive scheme popularized by Nick Saban and Bill Belichick.

As alluded to earlier, though, I mostly suspect we have a dearth of these kinds of movies because they are not a draw at the international box office. Gridiron football is not especially popular outside of the United States and, inexplicably, Germany.

But this may change soon. The European Football League (EFL) began in 2020 and has since expanded to 17 teams. By contrast, most minor league football leagues have historically struggled to maintain eight or even just six teams.

Granted, seven of the EFL’s teams are based in Germany with another in Austria, but there are also annual NFL games in the United Kingdom and Mexico (and also Germany), and there is now an annual season opening game of American college football played in Ireland. So at this rate I’d wager that by 2050 it will be financially viable to make a big budget movie with an animal playing football.

The only question is which position and which animal should be its focus. Here’s my pitch:

BIG PRIDE:

An arrogant talking lion is signed to play linebacker for the Detroit Lions, and along the way he learns to not only control his anger problem but also to not eat everything he tackles.

Naturally, I see The Rock playing the talking lion and Kevin Hart as his trainer.